One of life’s most difficult tasks is to look in the mirror—not just to see a reflection, but to confront the choices that shape who we are. That kind of deep self-examination requires patience, courage, and, more often than not, discomfort. For Basil Kincaid, the exploration of self isn’t a passing phase or philosophical pastime—it’s a necessity. His latest exhibition, Inward Cartography: Self of Selves, now on view at Library Street Collective in Detroit, is a striking meditation on the emotional and spiritual terrain of identity.

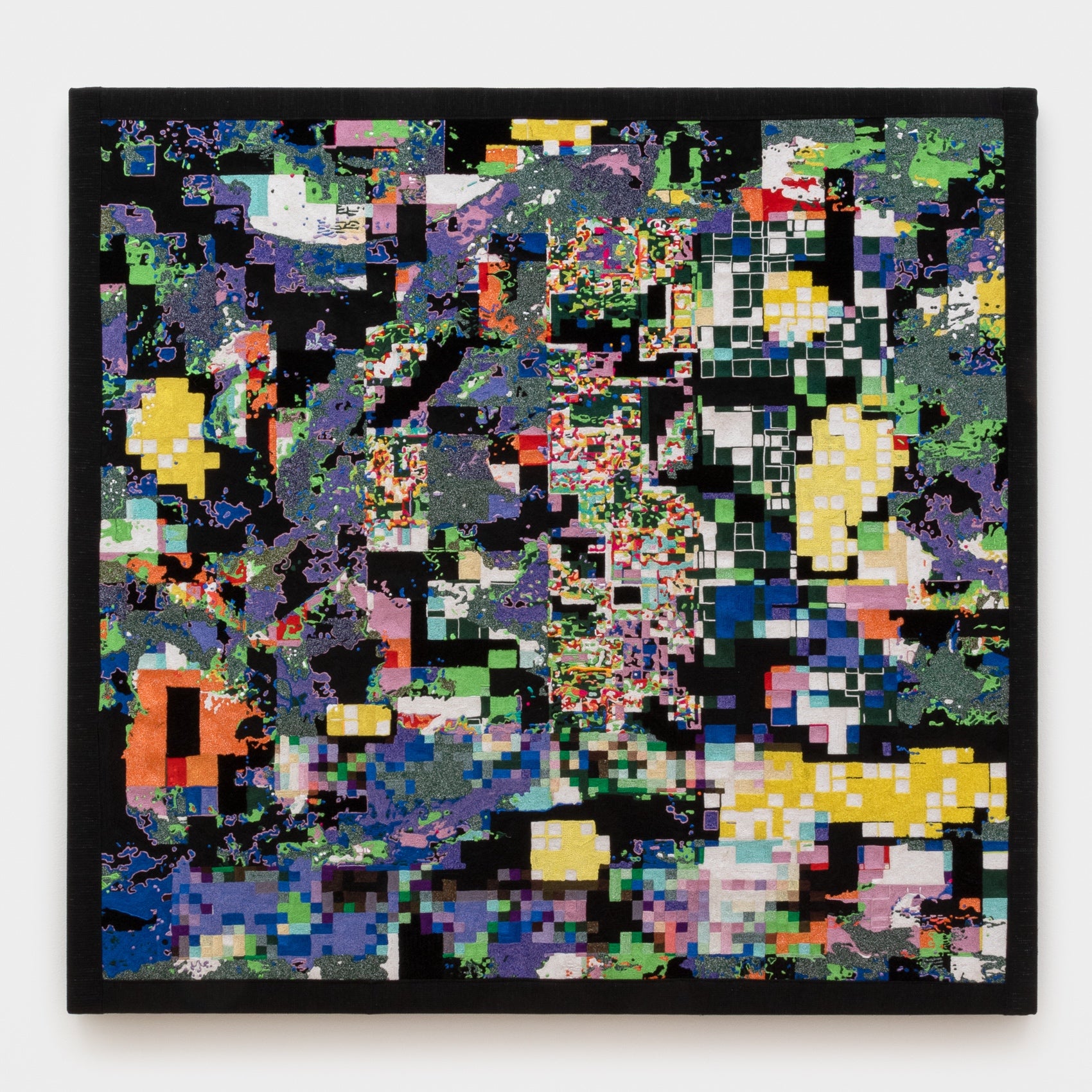

Known for richly layered textile works, Kincaid pushes beyond traditional forms to create pieces that serve as both portrait and process. Quilting, embroidery, drawing, digital rendering—these elements come together to create what he calls “fiber vignettes,” where color and composition come together to help the viewer, and artist, with personal assessment.

Crafted between studios in St. Louis and Ghana, the work is shaped by Kincaid’s constant movement across physical and psychological landscapes. He speaks openly about how location affects not just his art, but how he sees himself, and how he’s seen by others. “I’m looking at how my life changes and the perception of me changes based on where I am,” he explained. “There’s differences in how I’m perceived in [Missouri], if I’m just walking on the street versus how I’m perceived in the museum giving a speech—people look at me and experience me one way, and then the immediate experience changes their perception.”

That shifting view fuels many of the themes behind Inward Cartography. Each piece begins with a drawing, goes through a cycle of digital manipulation in Photoshop, then is embroidered and stretched like a canvas. Kincaid sees these media not as disparate, but as part of a continuum. “The way that the work is made brings in questions about place and how sites affect the way you think and operate and create,” the artist explained.

Kincaid’s hybrid method is also a deliberate rejection of the hierarchies that have long devalued certain materials or routines. “Drawing is often viewed as a lower form,” he noted. “But to me, it’s so foundational.” That sentiment extends to fiber art, which he insists deserves to be treated with the same seriousness and depth as any so-called fine art. In Basil’s hands, the Jacquard loom—a binary system of weaving from the 1800s—becomes a powerful metaphor for early computing, for structure, for storytelling.

“Arguments could be made that advancements in fiber art technology led to a type of social change in the way that we think that allows for the possibilities of computing and all these other things that we experience and depend on,” Kincaid said. “I feel like we exist in this sort of Venn diagram of realities where everybody has a digital cyber avatar or multiples across different social apps; you create these simulacra of yourself to present. As you create an image of yourself that you think is ideal and you put it into this thought space, it also impacts the way that you think of yourself, and that can be positive or negative based on how you react to the societal conditioning or the social norms of each of those various spaces.”

While Inward Cartography is deeply rooted in innovation, its core lies in what Kincaid calls “emotional defragmentation.” Much like a computer sorting its files to run more efficiently, Kincaid sifts through personal memories—both joyful and difficult—and reassembles them with intention. “The hardest is facing your mistakes; things you feel in retrospect you could have done better,” Basil shared. But instead of compartmentalizing those memories, he treats them as integral. Black shapes punctuate many of the works, symbolizing not absence, but weight. “When you try to forget a bad memory, you end up forgetting a lot of the memories around it that may have also been good,” he added.

In this landmark effort, the viewer is not just observing Kincaid’s journey—they are invited into their own. “I wanted this body of work to be less about storytelling and more about that process of wandering and wondering; experiencing the wilderness of yourself,” he said. This openness makes the exhibition feel less like an “art show” and more like a guided internal pilgrimage.

Literary influences—something newer in Basil’s creative practice—also run through this body of work. Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism gave language to some of the complexities Kincaid had been grappling with around multiplicity and existence. Octavia Butler, too, left a mark—not just through her storytelling, but through her fierce artistic discipline. “She had a clear determination that didn’t make room for excuses,” Kincaid reflected. “That pushed me to dig even deeper and give another layer of myself.”

And that’s exactly what Self of Selves offers: an unguarded layering of thought, process, and selfhood. The exhibition doesn’t seek to pin down identity, but to hold space for its contradictions. In a time when we often feel compelled to package and perform ourselves—digitally, socially, culturally—Kincaid resists that pull. Instead, the artist stitches together a series of work that is as intellectually rich as it is honest.

“Art is supposed to be the place of freedom,” Kincaid said. And in this exhibition, that freedom pulses through every thread, every shadow, and every map drawn from life’s encounters.

Inward Cartography: Self of Selves is on view through May 21, 2025 at Library Street Collective.